Eliza Effect and Gender Stereotypes

It would be unfair to discuss The Eliza Effect without crediting the various stories and myths that had hinted at a similar topic, long before AI was part of our lives. One such myth that I have always found fascinating is the myth of Pygmalion, or for the cinephiles, the movie My Fair Lady.

The myth is about a Cypriot sculptor who makes a sculpture of his ideal woman. He eventually goes on to fall in love with his creation and wishes to Aphrodite to make his bride a living likeness of his ivory girl, which she grants. The story then branches out, based on which edition we are referring to, some having a happy ending, while others do not.

This story is reminiscent to the modern tales of AI (or robots) gaining consiousnes and falling in love with a human. Ex Machina is probably the most recent and popular example for this trope. But this isn’t just a fictional trope anymore, we humans do tend to associate human qualities with machines and programs, even if we clearly know it’s not achievable (at least with the current system). Eliza Effect explains this very concept, where we associate qualities and attributes to a machine, purely based on its output.

Eliza Chatbot

Eliza was certainly a major milestone in making AI (even in it’s primitive form) accessible to regular users. Eliza was a NLP computer program designed at the MIT AI Laboratory and was named after Eliza Doolittle character from Shaw’s Pygmalion play (also the character name in ‘My Fair Lady’). It acted as a precursor to modern personal assistants like Google Assistant, Apple’s Siri etc.

Eliza acted as a mock psychotherapist, developed on top of a Doctor Script. It was able to converse with people, making up coherent sentences and asking questions that was generally expected from a therapist. While still a program at its core, Eliza grew more and more prominent among the public, as the questions often expressed a sense of understanding and compassion.

While ELIZA was by no means perfect, often ending up repeating sentences and struggling with emotion recognition and sentiment analysis. However, we probably should give it some slack as it was developed in 1960s, when computers weren’t as powerful and AI was still very young. You can check and play around with a version of Eliza in this link.

Eliza Effect

The Eliza Effect is an interesting concept in AI, where humans tend to unconsciously associate computer behavior with that of humans. This is when we associate outputs or results of computer with attributes and abilities it cannot possibly achieve. Let's consider Eliza as an example, it was a simple program that rephrased the user's response as questions. However, it surprisingly fared well when interacting with humans, with many claiming to understand the 'deeper meaning' behind the questions and Eliza's motivation. Funnily enough Eliza was never designed to invoke such reactions among the users.

The effect was noticeable even among individuals who are well aware of the deterministic nature of the output of the program. This was attributed to subtle cognitive dissonance, between users awareness of programming limitation and their reaction to the questions posed by the machine. This certainly had an impact in how people started to approach AI, rather than trying to pass Turing Test by explicit programming, people focussed on principles of Social Engineering.

Reinforcing Stereotypes

While Eliza Effect seems like merely another reactionary effect at surface level, at a deeper level we can notice that it reinforces the gender stereotypes we have build up in our heads. I’ve already discussed built-in bias in another post, so I’m going to focus only some more prominent and direct cases of stereotypes and bias here.

It’s probably not a mystery why many of the virtual assistant have female name or voice. When asked “What is you gender?” to voice assistants, it declines having any gender as its an AI. However having default female sound (although most have a wider array of choices now) only reinforces and encourages stereotypes of women being submissive and compliant.

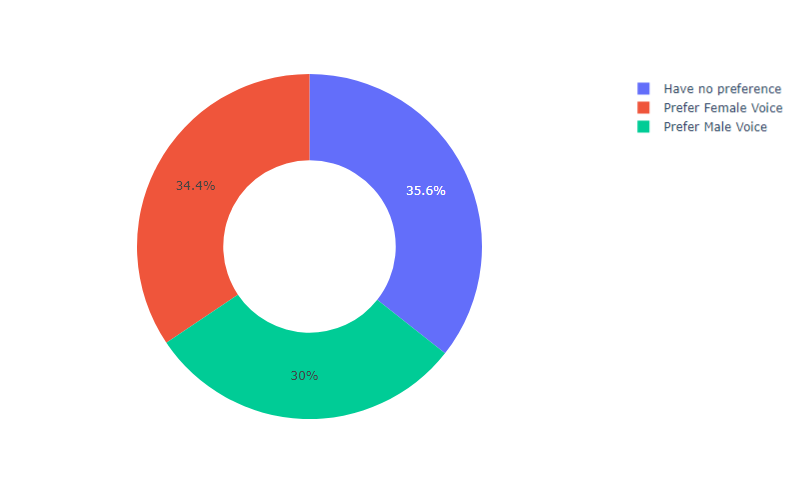

The argument that this is not stereotyping but rather merely satisfying the demand falls flat, considering a survey conducted by Real Researcher this year. We can see that the preference for having a Female Voice is actually a minority, further stressed by the fact that 80% of the responders believe that initiative taken by companies like Amazon and Apple to not make female voice default contributes towards gender equality.